THERE ARE TWO DIFFERENT USES OF THE WORD MYTH:

1. A story with metaphorical truth even if not factually accurate

2. A falsehood

Mythology preserves and transmits essential cultural truths by creating a realm which speaks to our present situation through timeless images and symbols. Humans interpret their world, their purpose, and their place in the world by means of myths. Gods, goddesses, heroes, heroines, giants, spirits, and demons act out the entire array of our internal and external existence. Through these stories, important lessons are taught and certain truths are established.

However, simple lies are often more popular than complex truths. Myths are often simplified, exaggerated, or otherwise changed to adapt to fit a certain climate. Popular misconceptions spread faster and root deeper than complex truth. They lead to an inaccurate, sometimes detrimental, interpretation of the world, and prevent people from seeking the truth.

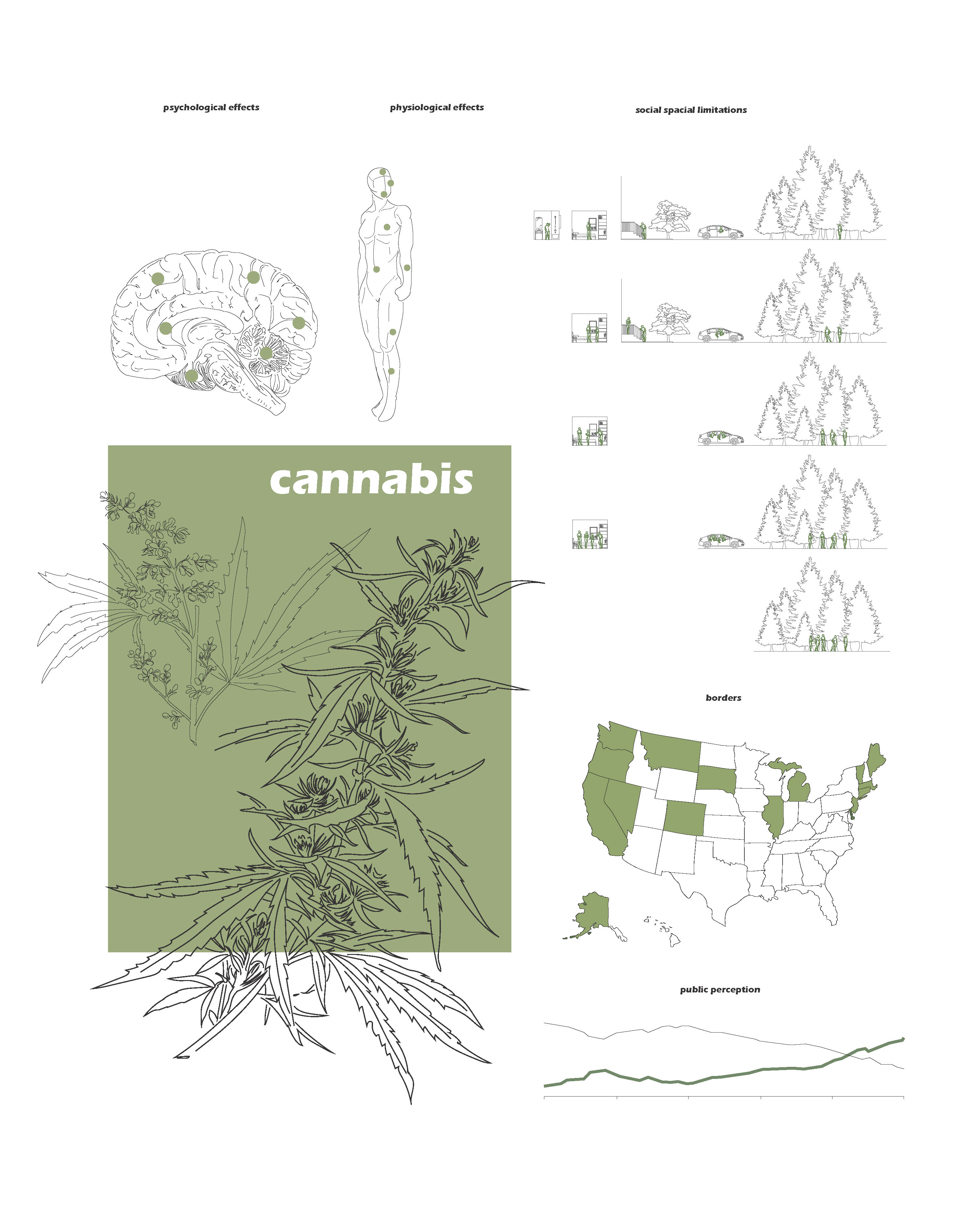

Popular untruths surrounding cannabis usage led to the criminalization of marijuana in the United States starting in the 1930s. While initial lack of information about the effect of the drug could have justified the panic and terror surrounding the drug, continued portrayal of the drug as malicious in newspapers, films, and other media dramatized the effects of the substance. A 1936 film, Reefer Madness, features a fictional take on the use of marijuana in which a trio of drug dealers elad innocent teenagers to become addicted to “reefer” cigarettes by holding wild parties with jazz music.

Racism also played a large role in the criminalization of marijuana. Racism towards Mexican immigrants in the 1930s who brought the plant to the United States worsened the relationship between the public and the substance. In addition, marijuana’s status as a Schedule I drug led to strict criminal justice policies that disproportionately affect black and Latinx Americans. A 2013 American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) study found that black Americans are nearly four times more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana possession, even though both groups use marijuana at comparable rates. Similarly, another study found that, between 2014 and 2016, 86 percent of people arrested for drug possession in New York City were black and Latino. Before Washington, D.C., legalized the recreational and medical use of marijuana, approximately 90 percent of Washingtonians who were arrested for possession of marijuana were black.

Another contribution to the criminalization of the drug was the threat of hemp replacing other profitable industries. From 1935 on, the Bureau of Narcotics, operated under the Secretary of the Treasury, actively rewrote the history of hemp by demonizing cannabis. The Secretary of the Treasury was Andrew Mellon at the time, a very powerful industrialist with interests in companies like DuPont, General Motors, and various oil interests. Mellon was well known to influence legislation in favor of big business. Mellon appointed Henry Anslinger (his niece’s husband) to head the FBN, and Anslinger wasted no time putting the bite on hemp. Soon after, the Bureau drafted the Marihuana Tax Act, which would place all cannabis under the control of Treasury Department regulations to limit and ultimately prohibit its cultivation and production.

Although myths that tell of metaphorical truths are no longer the center of life in modern societies, we still have rituals that are central to our communal and personal growth. Rituals are natural outgrowths of myths. So long as a ritual has the power to move one on a subliminal level, it retains its importance within the life of the community. Despite overwhelming evidence in the 1970s that cannabis usage is not harmful to health, it was categorized, and is still categorized as a Schedule I drug. This points to how pervasive and persuasive misconceptions can become, making a myth larger than life.

In the 1960s, experimentation with drugs were huge influences on the art and music of the time, but marijuana motifs had a special significance for cannabis users during an era in which consumption was a risky proposition. Mouse Miller, an american artist who produced posters for events and later produced promotional material for bands such as the Grateful Dead was one such artist who also made art for the psychedelic community. His 1966 poster promoting a benefit concert in California for a congressional candidate Phil Drath shows Winne the Pooh and his friend Piglet leading off into the sunset. Non users of cannabis would not notice the kilo Pooh is clutching in his left hand and Piglet blowing off a trail of smoke. Miller and many others attempted to change the visual library associated with cannabis usage, but were forced to do so with overt tactics.

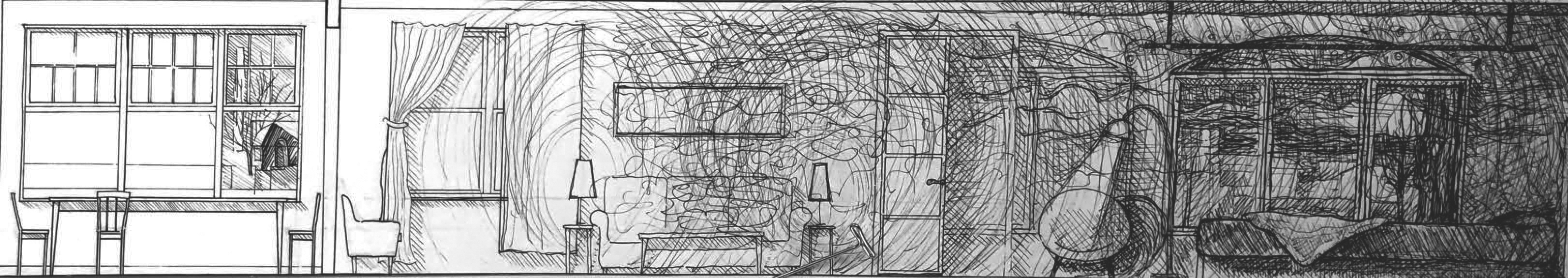

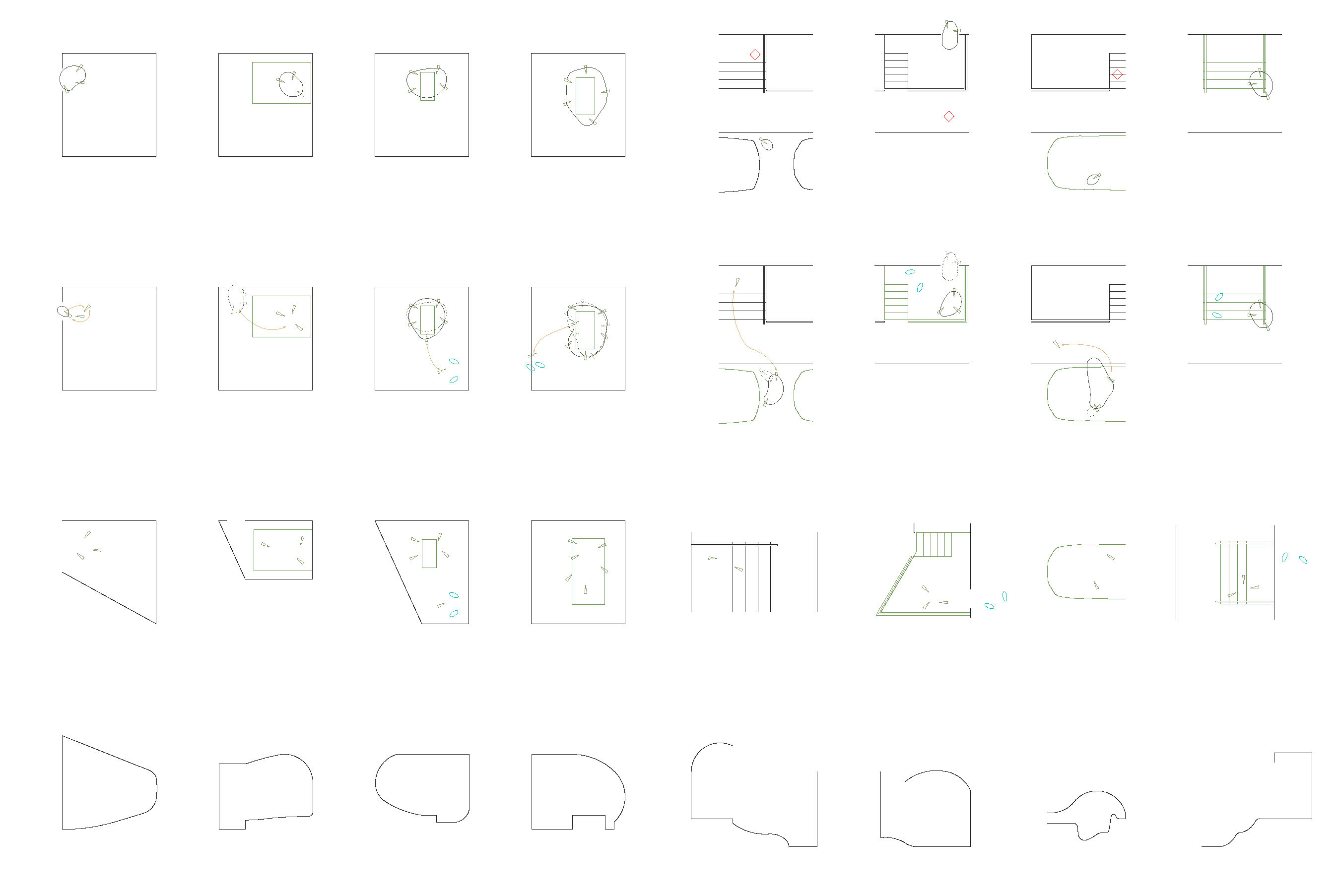

Despite efforts to change the portrayal of cannabis usage, the image of the stoners in their parents’ garage continues to live in the minds of many. This points to the damaging spatial preconceptions that continue to paint users as lazy, unmotivated, and ultimately useless in a society that prioritizes growth and production. How can the usage of cannabis be reappropriated and repaired to reeducate the masses about the effects of it?

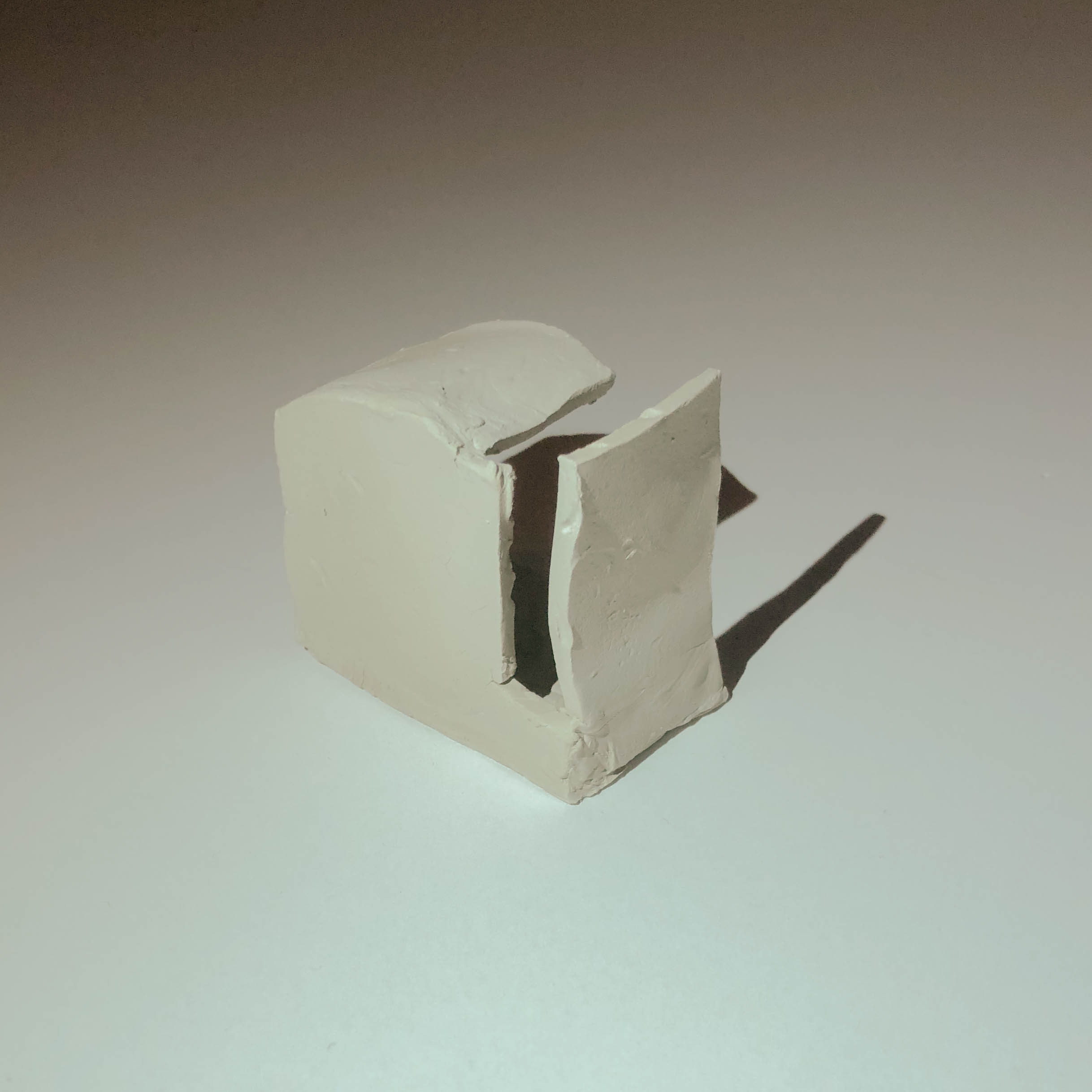

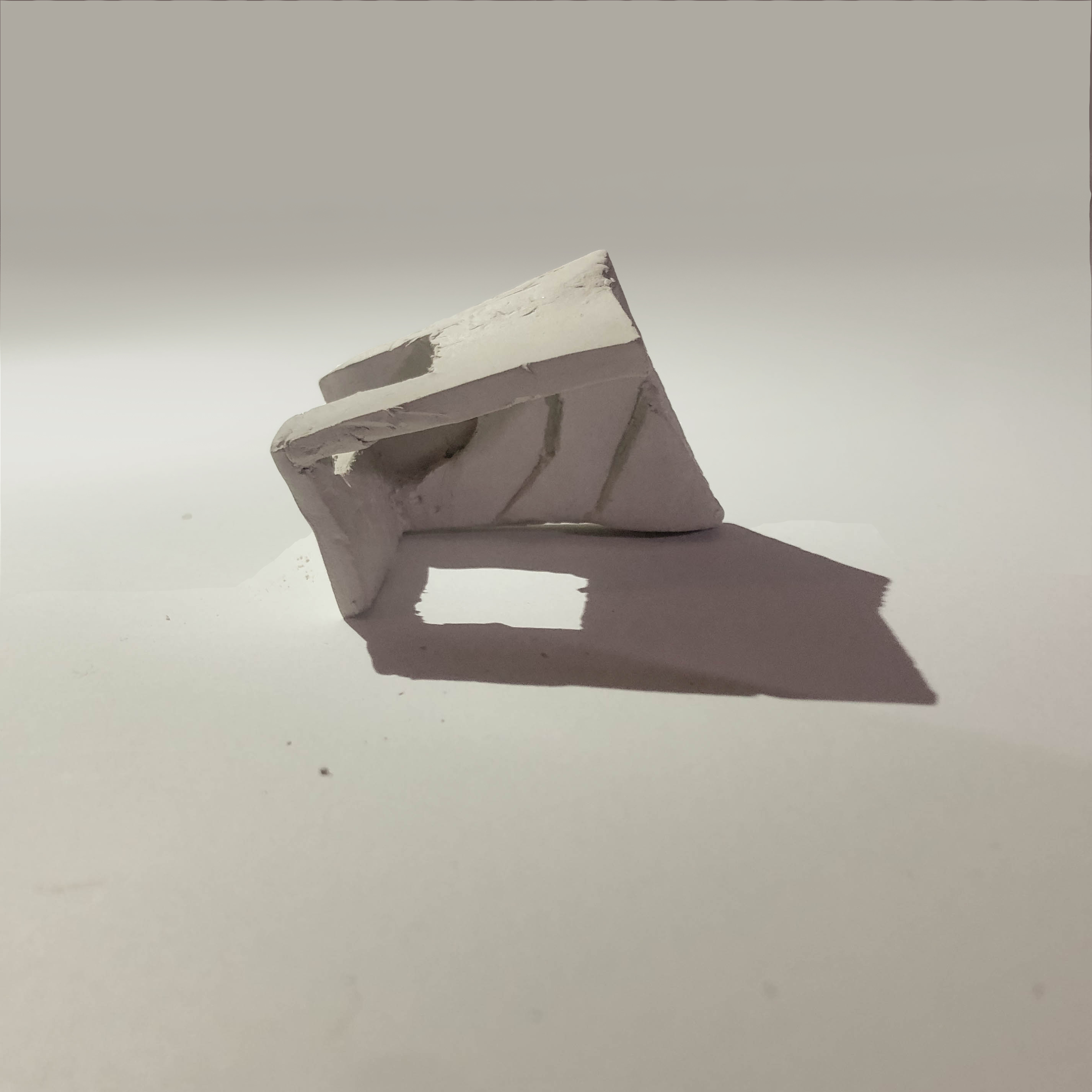

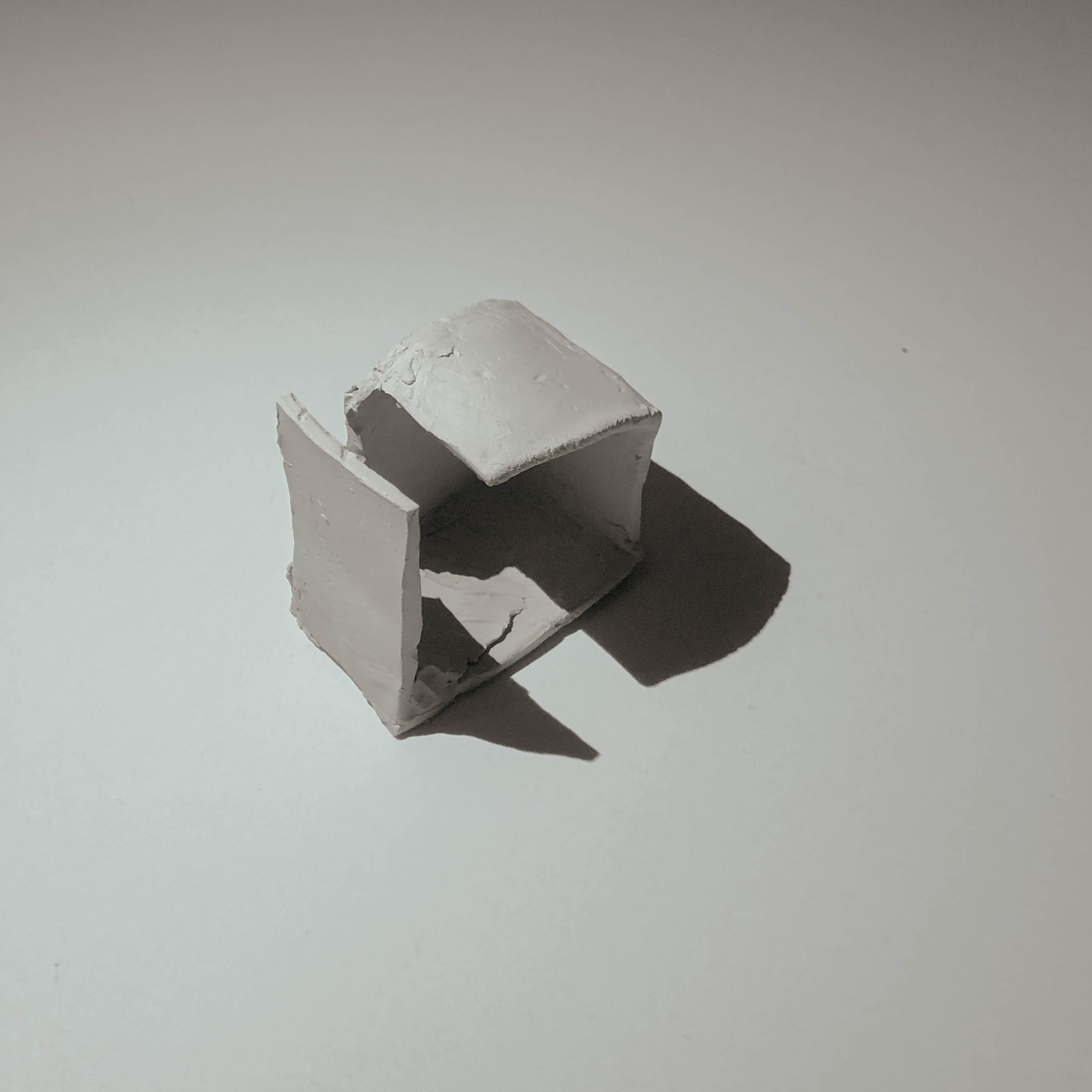

Processes of repair and reappropriation are seen in many different cultures. Kintsugi, the japanese art of repairing broken pottery, treats breakage and repair as a part of an object’s history rather than a flaw to disguise. In another context, Berbers, the indigenous populations of North Africa, made jewelry that included coins representing the queen or the emperor, the rulers of colonial empires like Napoleon or Queen Victoria. However, the front side was decorated with very typical red coral stone, hiding the faces of the rulers. In this case, the reappropriation can be interpreted as a counteraction in the process of repair.

As more states legalize marijuana, noticeably absent in most political campaigns to legalize marijuana at the state level - whether for medical or recreational use - is the racialized inception and enforcement of marijuana laws. Proponents for medical marijuana legalization have pointed to permissible medical uses for other illicit drugs such as opiates, and also to the compelling narratives of easing chronic pain, relieving nausea of cancer patients, and preventing seizures in epileptic children. Recreational legalization campaigns have emphasized the potential revenue gains of taxing marijuana sales, as well as honoring the individual liberty to use marijuana instead of the more dangerous alcohol. Rarely mentioned was the disproportionate burden of marijuana enforcement on racial minorities. Anecdotally, a Washington advocate for marijuana legalization told me that racial profiling arguments won't win legalization campaigns and instead will alienate voters.

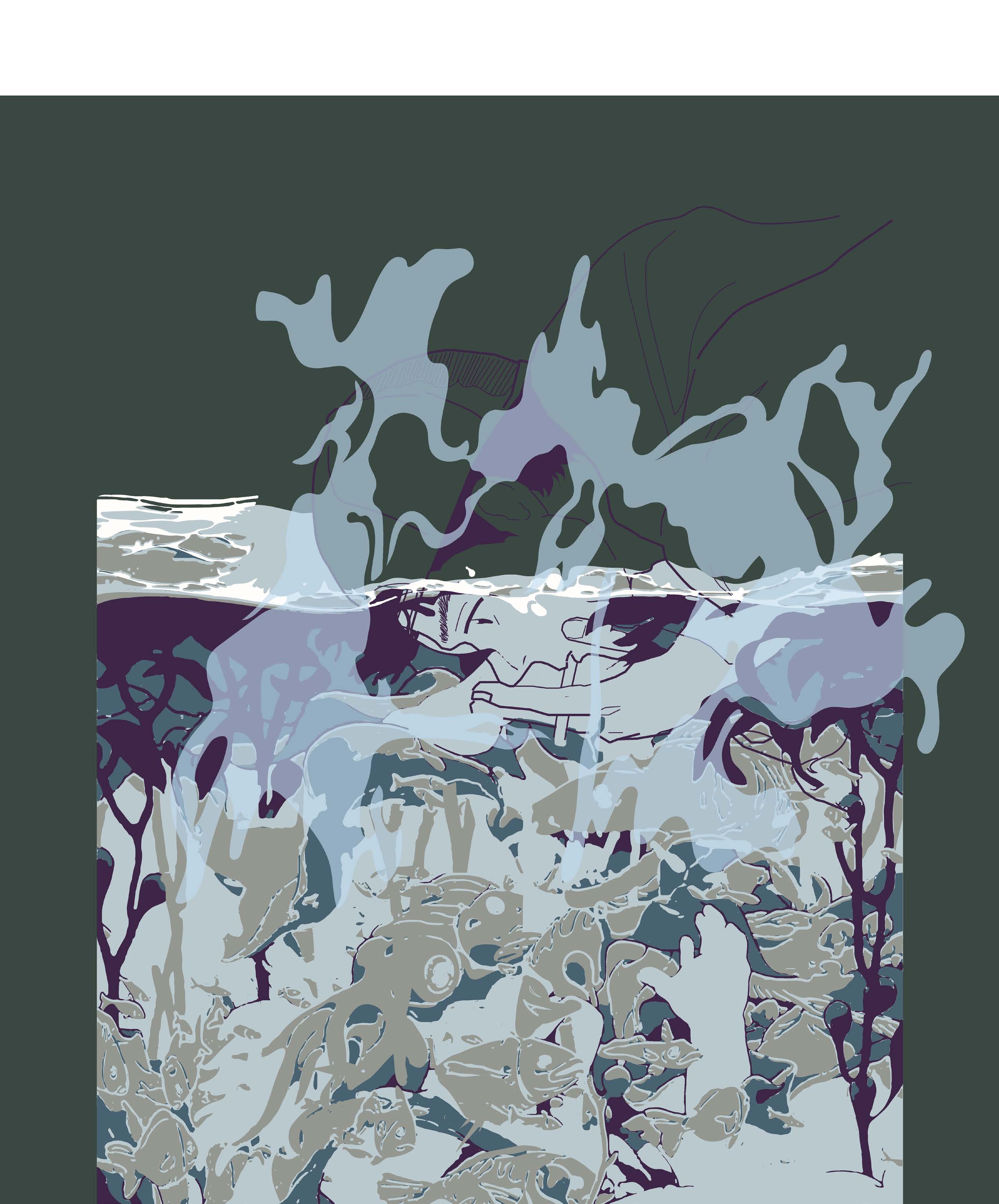

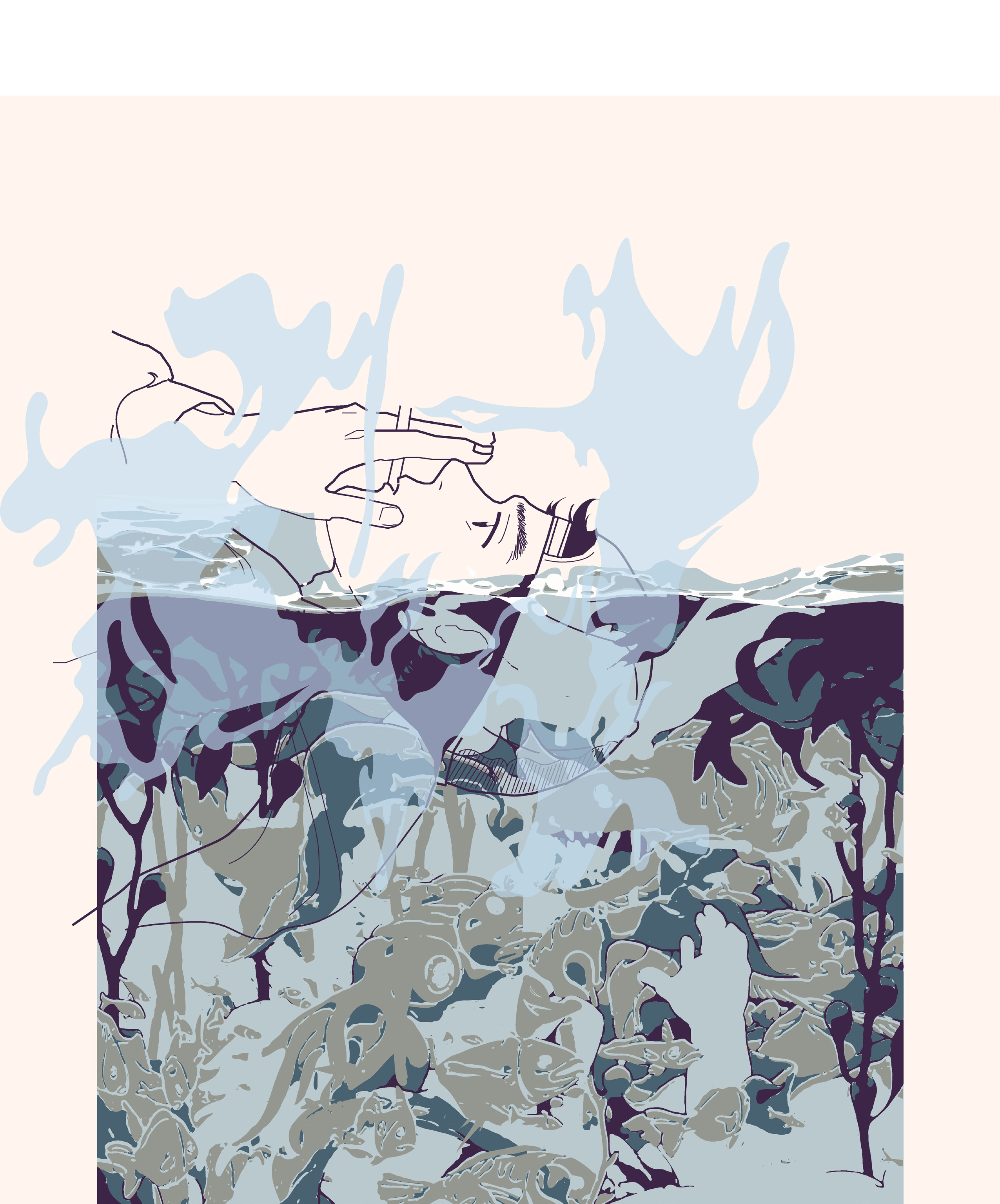

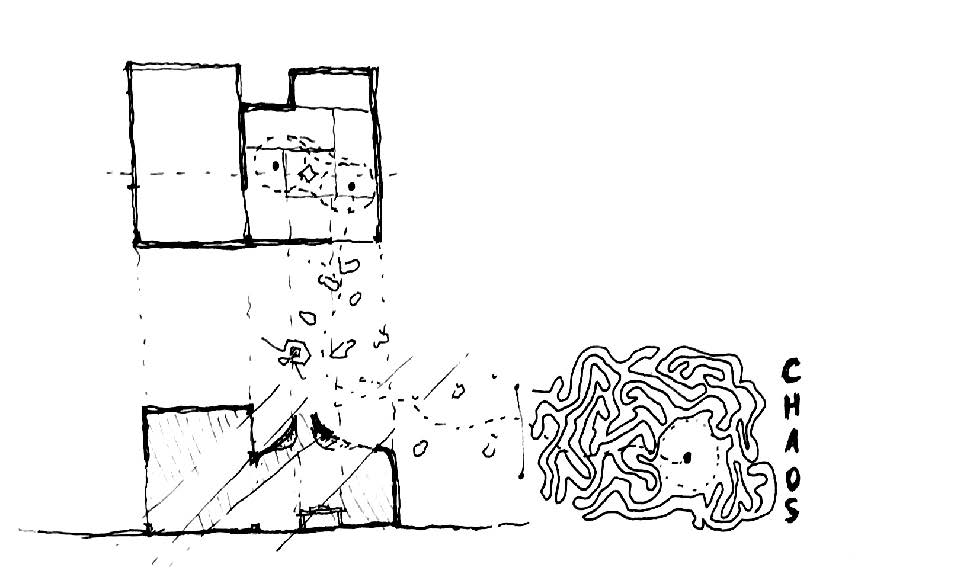

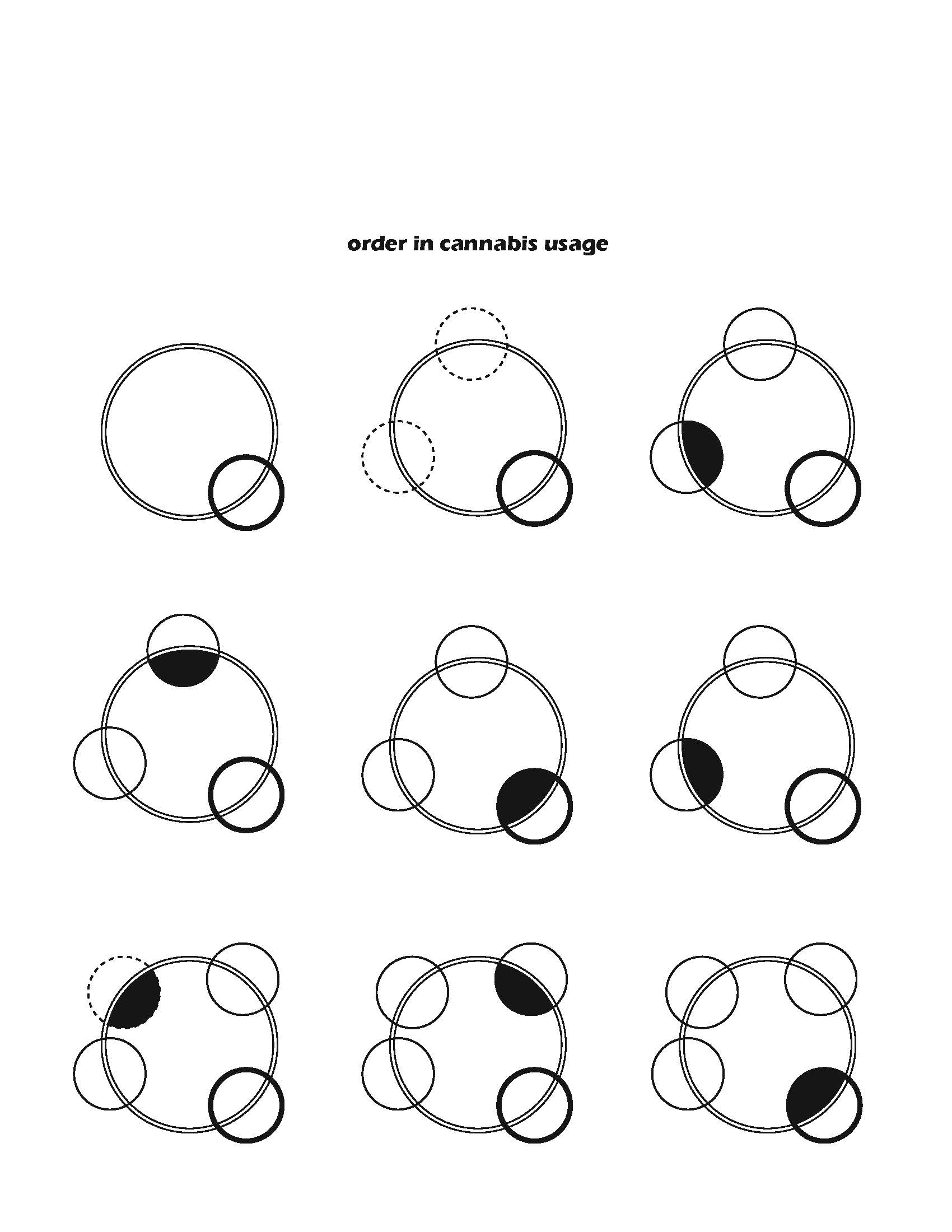

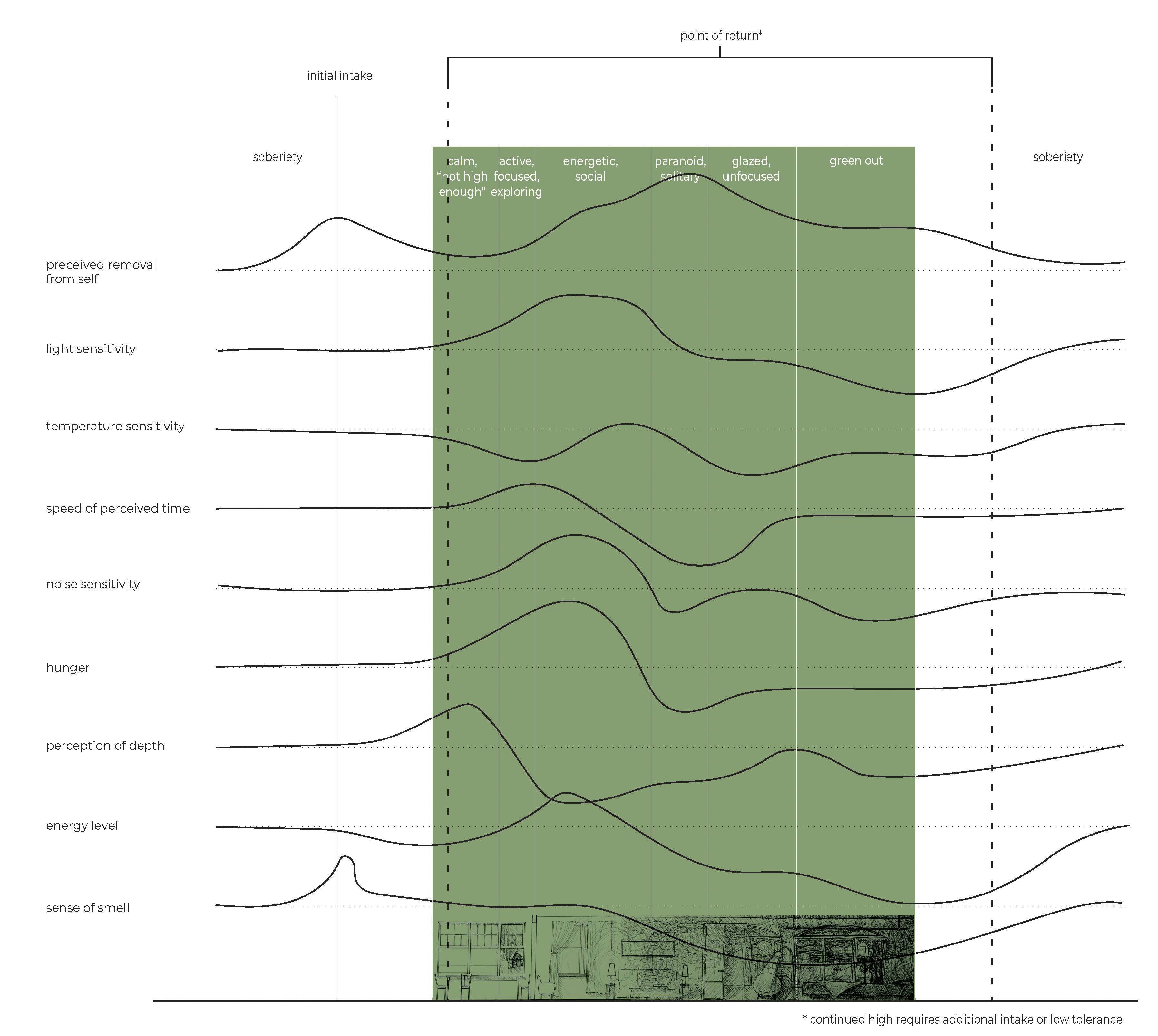

How can the history and demonization of marijuana be retold to include the full truth? The aim of this thesis is to reframe the context of weed usage, to create a new visual library and renew spatial preconceptions associated with cannabis usage, as well as allow for normal relationships between humans and substances. How can the consumption of cannabis be understood as a ritual, involving the picking, crushing, grinding, packing, and smoking of the flower? How can the mind altering effects of the drug be described, represented, and reappropriated so that irrational fear is not a reaction to marijuana?![]()

![]()

1. A story with metaphorical truth even if not factually accurate

2. A falsehood

Mythology preserves and transmits essential cultural truths by creating a realm which speaks to our present situation through timeless images and symbols. Humans interpret their world, their purpose, and their place in the world by means of myths. Gods, goddesses, heroes, heroines, giants, spirits, and demons act out the entire array of our internal and external existence. Through these stories, important lessons are taught and certain truths are established.

However, simple lies are often more popular than complex truths. Myths are often simplified, exaggerated, or otherwise changed to adapt to fit a certain climate. Popular misconceptions spread faster and root deeper than complex truth. They lead to an inaccurate, sometimes detrimental, interpretation of the world, and prevent people from seeking the truth.

Popular untruths surrounding cannabis usage led to the criminalization of marijuana in the United States starting in the 1930s. While initial lack of information about the effect of the drug could have justified the panic and terror surrounding the drug, continued portrayal of the drug as malicious in newspapers, films, and other media dramatized the effects of the substance. A 1936 film, Reefer Madness, features a fictional take on the use of marijuana in which a trio of drug dealers elad innocent teenagers to become addicted to “reefer” cigarettes by holding wild parties with jazz music.

Racism also played a large role in the criminalization of marijuana. Racism towards Mexican immigrants in the 1930s who brought the plant to the United States worsened the relationship between the public and the substance. In addition, marijuana’s status as a Schedule I drug led to strict criminal justice policies that disproportionately affect black and Latinx Americans. A 2013 American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) study found that black Americans are nearly four times more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana possession, even though both groups use marijuana at comparable rates. Similarly, another study found that, between 2014 and 2016, 86 percent of people arrested for drug possession in New York City were black and Latino. Before Washington, D.C., legalized the recreational and medical use of marijuana, approximately 90 percent of Washingtonians who were arrested for possession of marijuana were black.

Another contribution to the criminalization of the drug was the threat of hemp replacing other profitable industries. From 1935 on, the Bureau of Narcotics, operated under the Secretary of the Treasury, actively rewrote the history of hemp by demonizing cannabis. The Secretary of the Treasury was Andrew Mellon at the time, a very powerful industrialist with interests in companies like DuPont, General Motors, and various oil interests. Mellon was well known to influence legislation in favor of big business. Mellon appointed Henry Anslinger (his niece’s husband) to head the FBN, and Anslinger wasted no time putting the bite on hemp. Soon after, the Bureau drafted the Marihuana Tax Act, which would place all cannabis under the control of Treasury Department regulations to limit and ultimately prohibit its cultivation and production.

Although myths that tell of metaphorical truths are no longer the center of life in modern societies, we still have rituals that are central to our communal and personal growth. Rituals are natural outgrowths of myths. So long as a ritual has the power to move one on a subliminal level, it retains its importance within the life of the community. Despite overwhelming evidence in the 1970s that cannabis usage is not harmful to health, it was categorized, and is still categorized as a Schedule I drug. This points to how pervasive and persuasive misconceptions can become, making a myth larger than life.

In the 1960s, experimentation with drugs were huge influences on the art and music of the time, but marijuana motifs had a special significance for cannabis users during an era in which consumption was a risky proposition. Mouse Miller, an american artist who produced posters for events and later produced promotional material for bands such as the Grateful Dead was one such artist who also made art for the psychedelic community. His 1966 poster promoting a benefit concert in California for a congressional candidate Phil Drath shows Winne the Pooh and his friend Piglet leading off into the sunset. Non users of cannabis would not notice the kilo Pooh is clutching in his left hand and Piglet blowing off a trail of smoke. Miller and many others attempted to change the visual library associated with cannabis usage, but were forced to do so with overt tactics.

Despite efforts to change the portrayal of cannabis usage, the image of the stoners in their parents’ garage continues to live in the minds of many. This points to the damaging spatial preconceptions that continue to paint users as lazy, unmotivated, and ultimately useless in a society that prioritizes growth and production. How can the usage of cannabis be reappropriated and repaired to reeducate the masses about the effects of it?

Processes of repair and reappropriation are seen in many different cultures. Kintsugi, the japanese art of repairing broken pottery, treats breakage and repair as a part of an object’s history rather than a flaw to disguise. In another context, Berbers, the indigenous populations of North Africa, made jewelry that included coins representing the queen or the emperor, the rulers of colonial empires like Napoleon or Queen Victoria. However, the front side was decorated with very typical red coral stone, hiding the faces of the rulers. In this case, the reappropriation can be interpreted as a counteraction in the process of repair.

As more states legalize marijuana, noticeably absent in most political campaigns to legalize marijuana at the state level - whether for medical or recreational use - is the racialized inception and enforcement of marijuana laws. Proponents for medical marijuana legalization have pointed to permissible medical uses for other illicit drugs such as opiates, and also to the compelling narratives of easing chronic pain, relieving nausea of cancer patients, and preventing seizures in epileptic children. Recreational legalization campaigns have emphasized the potential revenue gains of taxing marijuana sales, as well as honoring the individual liberty to use marijuana instead of the more dangerous alcohol. Rarely mentioned was the disproportionate burden of marijuana enforcement on racial minorities. Anecdotally, a Washington advocate for marijuana legalization told me that racial profiling arguments won't win legalization campaigns and instead will alienate voters.

How can the history and demonization of marijuana be retold to include the full truth? The aim of this thesis is to reframe the context of weed usage, to create a new visual library and renew spatial preconceptions associated with cannabis usage, as well as allow for normal relationships between humans and substances. How can the consumption of cannabis be understood as a ritual, involving the picking, crushing, grinding, packing, and smoking of the flower? How can the mind altering effects of the drug be described, represented, and reappropriated so that irrational fear is not a reaction to marijuana?